The Silent Struggle of Pakistan’s Working Children

In the wheat fields of southern Punjab, 12-year-old Hassan* bends low, harvesting crops under a merciless sun. He no longer attends school. “I went for a while,” he says quietly, “but we needed money.” His story echoes across thousands of homes in Pakistan, where poverty and social norms still push children into the workforce—and keep them there.

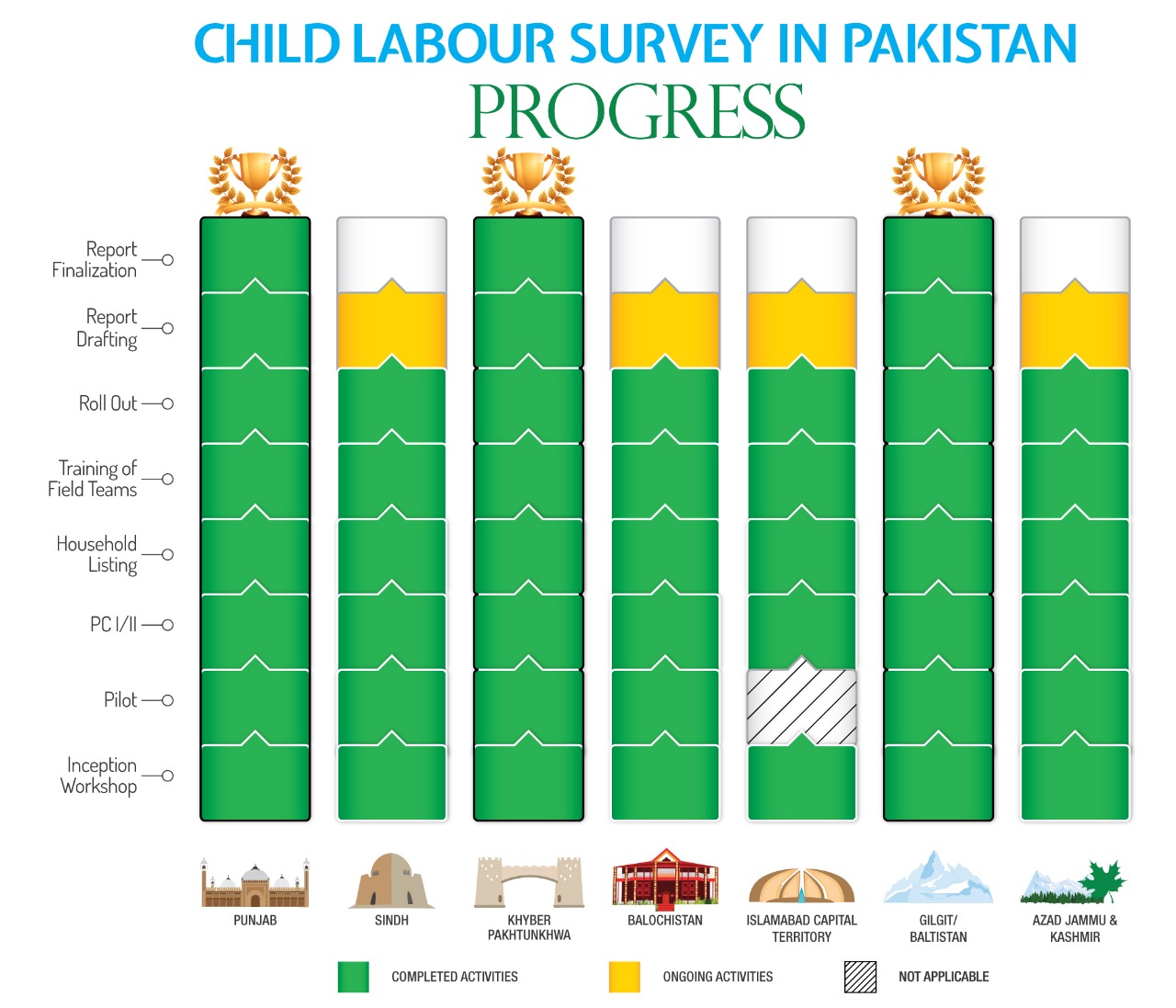

Pakistan has long acknowledged the scourge of child labour. In 1996, a national survey by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) found that 3.3 million children aged 5–14 were engaged in economic activity. Of these, 2.4 million were boys and 0.9 million girls, with most working in agriculture (66%), followed by manufacturing (11%) and services (9%). But for nearly three decades, no updated national data has been collected, forcing provinces to take up the task individually.

A Provincial Picture Emerges: Where Children Work and How

Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province, the 2019–20 Punjab Child Labour Survey, conducted by PBS with support from the International Labour Organization (ILO), found that 13.4% of children aged 5–14 were working. This number rose to 16.9% when including older children up to age 17. Alarmingly, 47.8% of working children aged 10–14 were in hazardous occupations such as handling machinery, exposure to chemicals, or long hours without safety precautions.

Sahiwal district had the highest rate of child labour (24.7%) ; ILO

The survey revealed deep regional divides: Sahiwal district had the highest rate of child labour (24.7%), while Rawalpindi had the lowest (6.1%). The majority 55.3% were employed in agriculture, followed by manufacturing (13.6%) and wholesale/retail work.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the 2022 Child Labour Survey, also by PBS and ILO, found that 9% of children aged 5–17 were working. While lower than Punjab’s rate, the danger was greater: an estimated 73.8% of these children were involved in hazardous labour. Most were engaged in elementary occupations (61.6%) like street vending, waste collection, or heavy lifting, often without any regulation or protection.

Gilgit-Baltistan, the 2018–19 child labour survey reported that 13.1% of children aged 5–17 were economically active, with the number jumping to 23.7% for children aged 14–17. Over 76% of these children worked in agriculture and forestry, typically without school attendance. The survey, conducted by PBS with technical support from ILO, also noted that 28.7% of working children were not in school at all.

About 3.3 million of Pakistani children are trapped in child labor, depriving them of their childhood, their health and education, and condemning them to a life of poverty ; UNICEF

Data from ILOSTAT, the ILO’s global statistics portal, estimates that nationwide, only 0.8% of working children aged 10–14 in Pakistan continue their education while working. School attendance is 15% lower among girls than boys, especially in rural areas, where cultural barriers and early marriage further reduce access to education.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s 2022 report on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, children in Pakistan are frequently found working in hazardous sectors such as brick kilns, carpet weaving, surgical instruments manufacturing, domestic servitude, and street begging. Many of these jobs pose severe physical and psychological risks and are not regulated by any form of labour inspection or enforcement.

Preventing Child Labour: Laws, Policies, and Where They Fail

Pakistan has ratified key international conventions against child labour, including ILO Conventions 138 and 182, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 25-A of the Constitution guarantees free and compulsory education for all children aged 5–16, while various national and provincial laws restrict child labour.

The Employment of Children Act, 1991, was the first major law to prohibit employment of children under 14 in hazardous occupations. Provinces have since adopted their own updated versions—such as the Punjab Restriction on Employment of Children Act, 2016, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Prohibition of Employment of Children Act, 2015—which include penalties for violations and ban dangerous forms of child labour. In theory, these laws are robust. In practice, enforcement is weak.

Labour inspectors are under-resourced and rare, especially in rural areas. Many sectors that employ children operate in the informal economy, making monitoring difficult. Most child labour occurs inside homes, on family farms, or in workshops that are unregistered and invisible to official oversight.

There have been some positive steps. The provincial child labour surveys themselves represent a move toward evidence-based policy. Punjab launched rehabilitation centres for rescued children and has initiated school stipend programs to reduce dropouts. But these efforts are often underfunded, inconsistent, or restricted to urban centres.

As of 2023, StateOfChildren.com reported that over 22.8 million children in Pakistan are out of school

Critics also point out the lack of a nationally coordinated child labour strategy. Without alignment between provincial and federal bodies, responses remain fragmented. Structural poverty, inflation, lack of social protection, and large out-of-school populations continue to feed the cycle.

As of 2023, StateOfChildren.com reported that over 22.8 million children in Pakistan are out of school, the second highest number globally. Without urgent, systemic reforms to make education accessible and economically viable for poor families, the country’s child labour problem is likely to worsen.

For children like Hassan, promises of protection and education ring hollow. His story is one of many untold, buried beneath the weight of economic desperation and institutional neglect. Until Pakistan treats child labour not just as a legal issue but as a humanitarian emergency millions more childhoods will continue to be lost.