Alarming HIV Surge in Pakistan Fueled by Unsafe Practices and Stigma

Health Minister Dr. Azra Pechuho was informed on Tuesday that the spread of HIV in Sindh had reached an “extremely alarming” level, with 3,995 registered HIV-positive children in the province.

A high-level meeting on the alarming rise of HIV cases across Sindh was chaired by the health minister. She was briefed by officials that more than 600,000 quack doctors are operating in Sindh, 40 percent of them in Karachi alone.

The officials said that major causes of the spread of HIV include unregulated and unethical medical practices, unsafe blood transfusions, illegal clinics, unregistered blood banks, reuse and repackaging of syringes, contaminated injections, cannula centers, reuse of razors by barbers, sale of hospital waste, unscreened blood, and unsafe dental tools.

The minister issued strict directives to all SSPs and deputy commissioners to immediately shut down illegal health facilities and take decisive action against quackery and unsafe medical practices. She ordered mandatory screening of pregnant women to prevent any mother-to-child virus transmission. She instructed the Sindh Healthcare Commission (SHCC) and police to ensure that sealed healthcare units would not reopen.

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system by destroying CD4 cells (a type of white blood cell), which help fight off infection.

This is not new. The Taunsa outbreak in South Punjab surfaced publicly in March–April 2025 after children began testing positive in worrying numbers. Early local reports put the initial confirmed child cases around 50, sparking mass screening operations that tested thousands; an expert mission later reported that some 5,400 people were screened in the Taunsa area, with dozens of suspected positive cases and hundreds of quack-run centers sealed. Health authorities said the cluster appeared linked to unsafe injection practices in informal and poorly regulated clinical settings.

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system by destroying CD4 cells (a type of white blood cell), which help fight off infection. A person is diagnosed with AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) when the immune system has been severely weakened by HIV. For transmission to occur, these fluids must enter the bloodstream of an HIV-negative person, which can happen in the following ways: unprotected sex engaging in anal or vaginal sex without a condom or HIV prevention medicine carries the highest risk.

The virus can enter the body through the lining of the rectum, vagina, or penis. Sharing needles sharing drug injection equipment, such as needles and syringes, can transmit HIV and other infectious diseases like hepatitis. Mother-to-child transmission an HIV-positive pregnant person can pass the virus to their baby during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding.

However, receiving treatment during pregnancy can greatly reduce this risk. Unsafe medical practices in countries without rigorous blood safety standards, HIV can be transmitted through unscreened blood transfusions. Improperly sterilized medical instruments for procedures like surgery, tattoos, and piercings can also spread the virus. HIV is not transmitted through casual contact like kissing, hugging, or sharing food or drinking glasses.

Pakistan is considered a country with a low-prevalence, concentrated epidemic, but it faces significant challenges that put it at risk for a wider outbreak. Some 2025 reports indicate a worrying surge in new infections, and the country has been listed second among Asia-Pacific nations with the sharpest rise in HIV cases.

When R, a 32-year-old transgender woman from Multan, first fell ill, she thought it was exhaustion from long working nights and stress. “I was losing weight fast, and every doctor I went to gave me tonics or painkillers,” she recalled softly. It wasn’t until she collapsed and was taken to a government hospital that she was tested for HIV months too late. “The nurse looked at my report and whispered to another staffer, ‘yeh to aisi hai (she’s one of those), of course she has HIV.’ From that day, no one touched me without gloves.”

“Sex and sexuality are treated as taboo topics something shameful,” Uzma Yaqoob, head of the FDI organisation, told The Reporters. “People are condemned or socially boycotted for even discussing them.

Her diagnosis didn’t just change her health , it ended her sense of belonging. Her family cut contact, neighbors whispered, and even within her own transgender community, she felt isolated. “People think we deserve it because of who we are,” she said. “But no one asks where we got it , from reused needles, unsafe blood, or just being denied care.”

“Sex and sexuality are treated as taboo topics something shameful,” Uzma Yaqoob, head of the FDI organisation, told The Reporters. “People are condemned or socially boycotted for even discussing them. This shame and stigma delay diagnosis, discourage people from seeking treatment, and prevent them from accessing age-appropriate, accurate information.”

Yaqoob criticized the lack of comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in schools. “We don’t allow children to learn about their bodies and relationships in a healthy way,” she explained. “Instead, we rebrand it as life skills-based education, which dilutes its purpose. Without proper information from an early age, young people can’t make safe choices or understand the importance of prevention and diagnosis.”

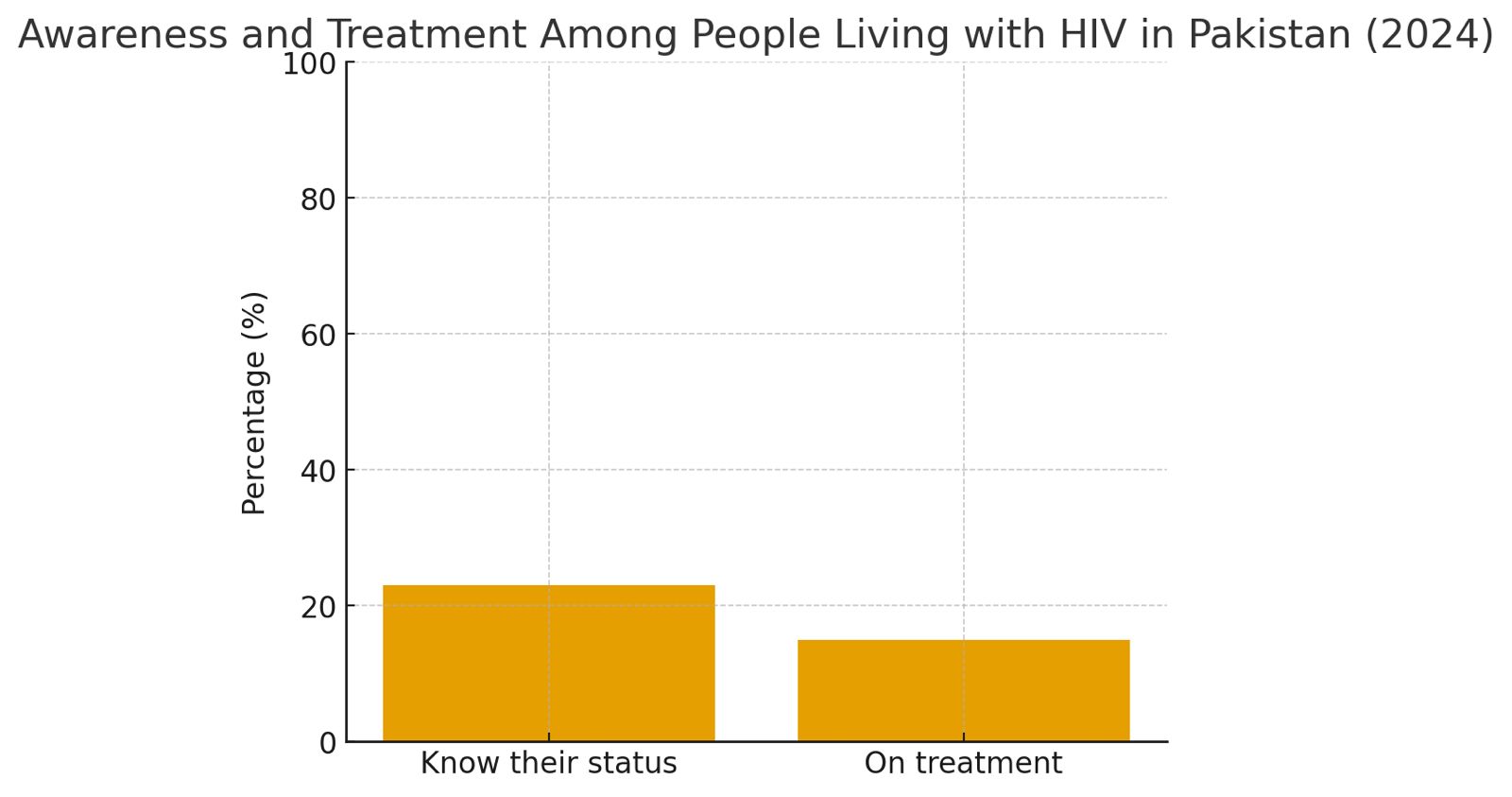

Pakistan’s struggle against HIV stands at a crossroads one marked by alarming infection trends but also renewed global support. According to the UNDP, an estimated 290,000 people in Pakistan are living with HIV, yet only 23 percent know their status and 15 percent are on treatment, underscoring the depth of the crisis.

Over recent years, repeated outbreaks from the 2019 Larkana tragedy to the Taunsa cluster of HIV-positive children and Nishtar Hospital’s contaminated dialysis equipment have exposed systemic negligence, unsafe medical practices, and poor regulatory oversight in healthcare settings.

Despite these setbacks, the UNDP-led Global Fund HIV programme, in partnership with the Ministry of Health and provincial departments, has made measurable progress, expanding community-led prevention sites from 19 to 53 across 19 cities, and reaching over 1.3 million vulnerable individuals by 2024 through mobile outreach and community initiatives. Yet, low ART retention and ongoing stigma continue to block Pakistan’s path toward the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets.

As Moon Ali of the Khawaja Sira Society notes, “From awareness campaigns to PrEP advocacy, communities have played a vital role in reducing HIV stigma and improving treatment access.” The road ahead demands not just international funding but a national reckoning , in hospital accountability, infection control, and public health trust to ensure that HIV prevention and treatment become a right, not a privilege, for all Pakistanis.

When A, walked into a government hospital last year for a routine dialysis session, he had no idea that the very machines meant to sustain his life would alter it forever. A few months later, his health began to deteriorate rapidly. Multiple tests later, doctors told him he had tested HIV positive.

“I had never touched drugs, never had risky behavior,” he said quietly, staring at his trembling hands. “But everyone even my own family began looking at me differently. They said I must have done something wrong.” His wife left him; his employer asked him to “take leave until things settle.”

The shame was crushing, the whispers relentless. It was only later that an internal inquiry revealed that unsterilized dialysis and respiratory machines at Nishtar Hospital had infected several patients with HIV and other bloodborne diseases. Ali’s story is not an isolated tragedy ,it is part of a widening crisis that Pakistan’s health system has failed to contain.

“Structural reforms must begin with the recognition and protection of gender minorities,” Yaqoob explained. “Pakistan has already taken an important step with the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2018. But we also need to recognize that other marginalized groups , women with disabilities, women from religious and ethnic minorities, and young people are equally important. These groups are not only in need of services but are also at a higher risk of contracting HIV and other infections.”

She emphasized that laws must translate into actionable policies and budgets. “Integrating legislation into national policies and linking those policies with resource allocation is critical,” she said. “Without funding, even the best laws and policies remain meaningless. If resources aren’t attached, services can’t be inclusive or effective money matters the most.”

Yaqoob believes that inclusivity in policymaking is key to sustainable change. “People representing gender minorities, especially transgender persons, women with disabilities, and young people, should be part of policy-making and budgetary discussions,” she noted. “Only when affected communities have a seat at the table can services truly become inclusive.”Moving to the social and cultural barriers, she pointed out that Pakistan’s deeply rooted patriarchal attitudes and rigid gender norms severely hinder early diagnosis and prevention.

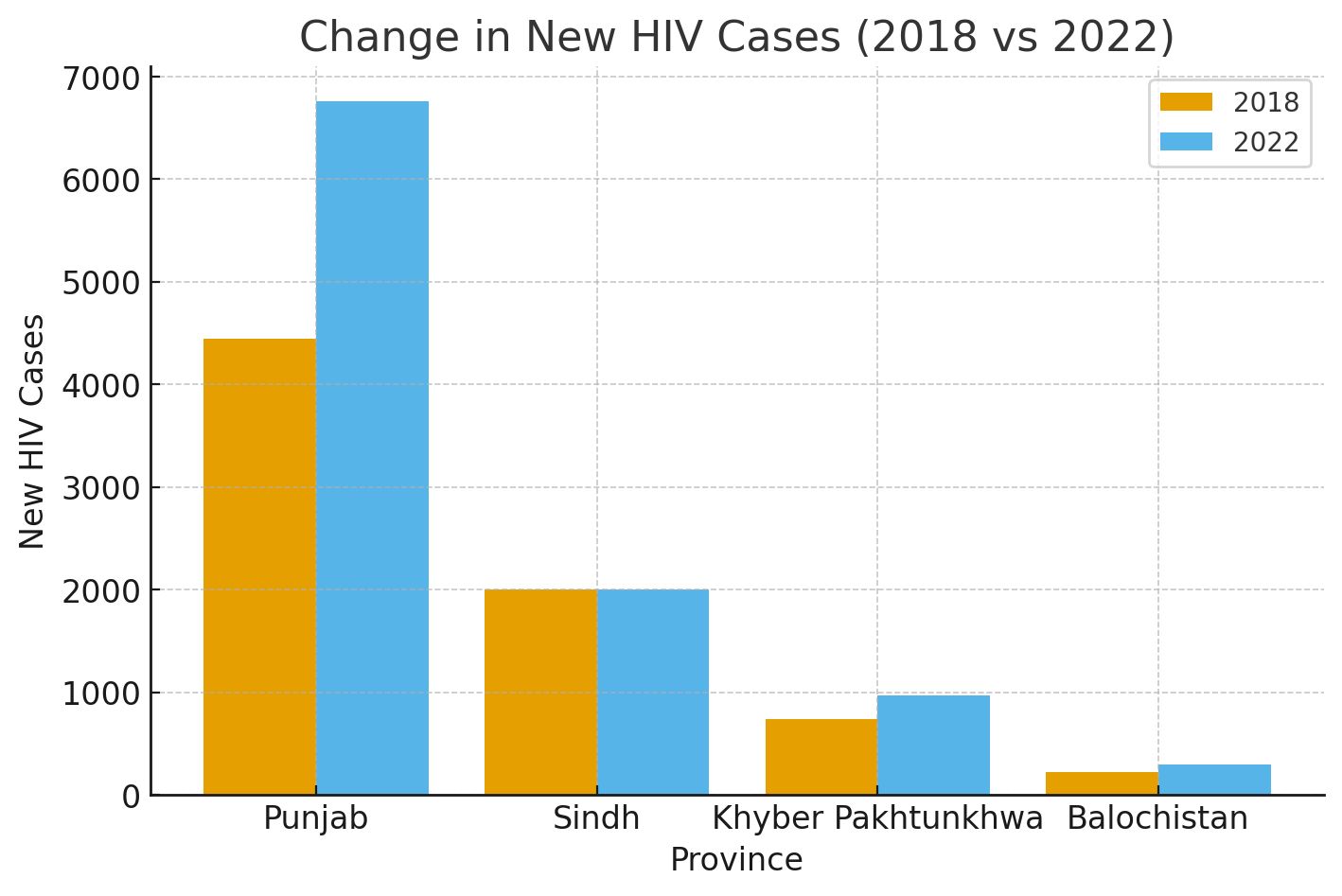

between 2018 and 2022. Punjab recorded the highest surge, with new HIV cases rising from 4,445 in 2018 to 6,762 in 2022

According to official data obtained by The Reporters through the Right to Information (RTI) Act, HIV cases in Pakistan have shown a deeply troubling upward trend between 2018 and 2022. Punjab recorded the highest surge, with new HIV cases rising from 4,445 in 2018 to 6,762 in 2022 , a jump of more than 50 percent in just five years. Sindh followed with a relatively stable but persistently high infection rate, moving from 2,073 to 2,059 cases, reflecting either improved control or continued underreporting.

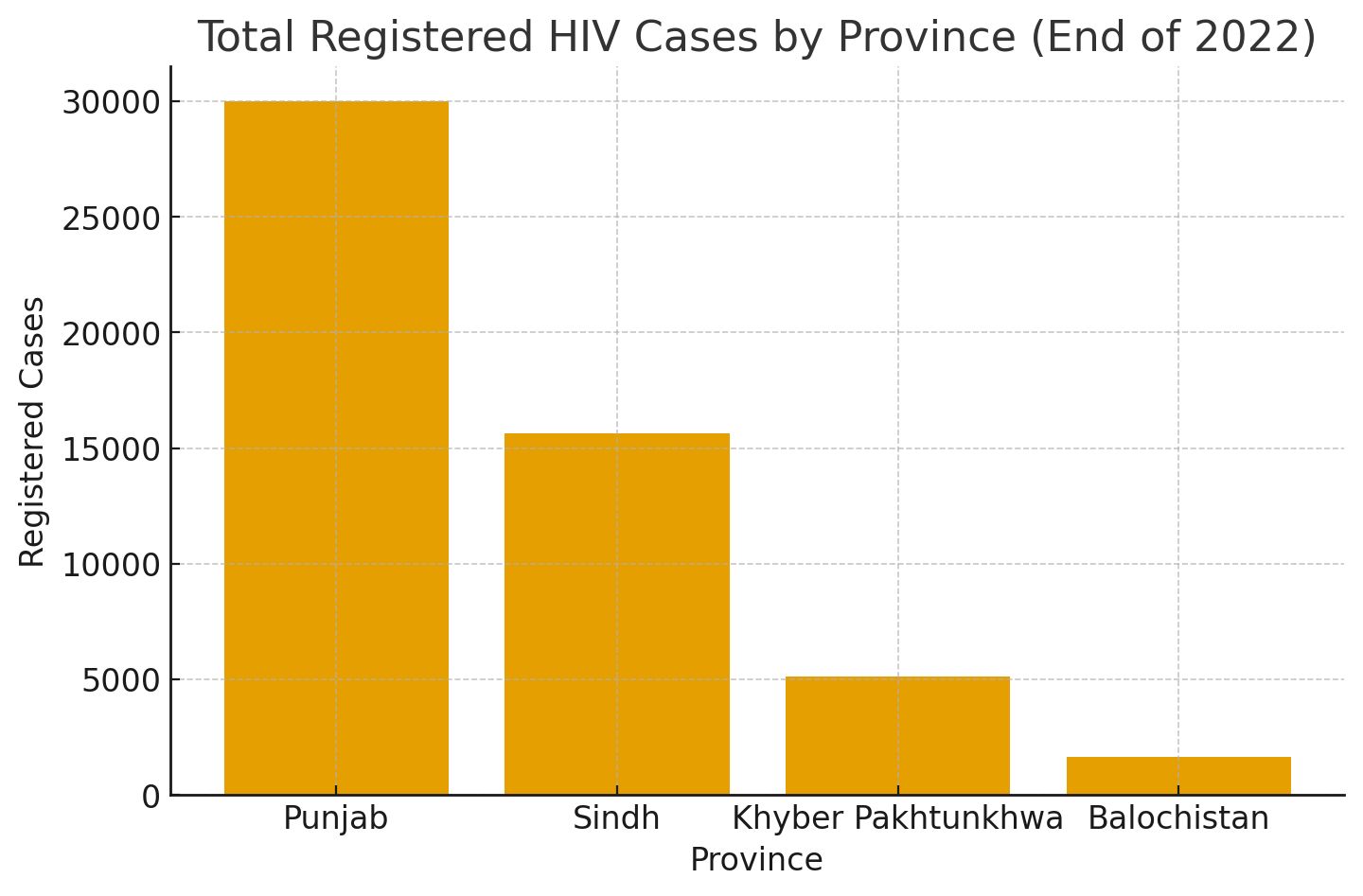

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa witnessed almost a twofold increase in cases (from 738 to 972), while Balochistan saw a modest rise from 221 to 296. As of December 2022, total registered HIV cases stood at over 30,000 in Punjab, 15,639 in Sindh, 5,138 in KP, and 1,659 in Balochistan. Among high-risk populations, People Who Inject Drugs (PWIDs) remain the most affected group, particularly in Sindh where infections exceed 4,000.

The data also reveals a worrying pattern of vulnerability among transgender persons (TGs) across all provinces. Overall, this RTI data positions Punjab as the epicenter of Pakistan’s HIV epidemic, while Sindh and KP continue to face localized outbreaks linked to unsafe injection practices, poor healthcare regulation, and stigma that discourages testing and treatment.

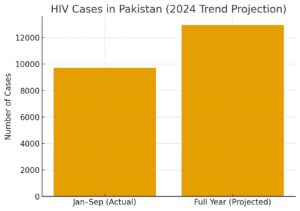

A report published in The News in 2024 shows some official figures and stated that as many as 1,079 new HIV cases are being reported monthly in Pakistan, with 9,713 people testing positive for HIV in the first nine months of 2024, officials in the Ministry of National Health Services revealed on Friday.

They warned that the total number of HIV cases for the entire year could exceed 12,950, assuming the current monthly average persists. This marks a significant increase compared to the 12,731 total cases reported throughout 2023, indicating a worsening HIV epidemic in Pakistan that demands immediate public health intervention.

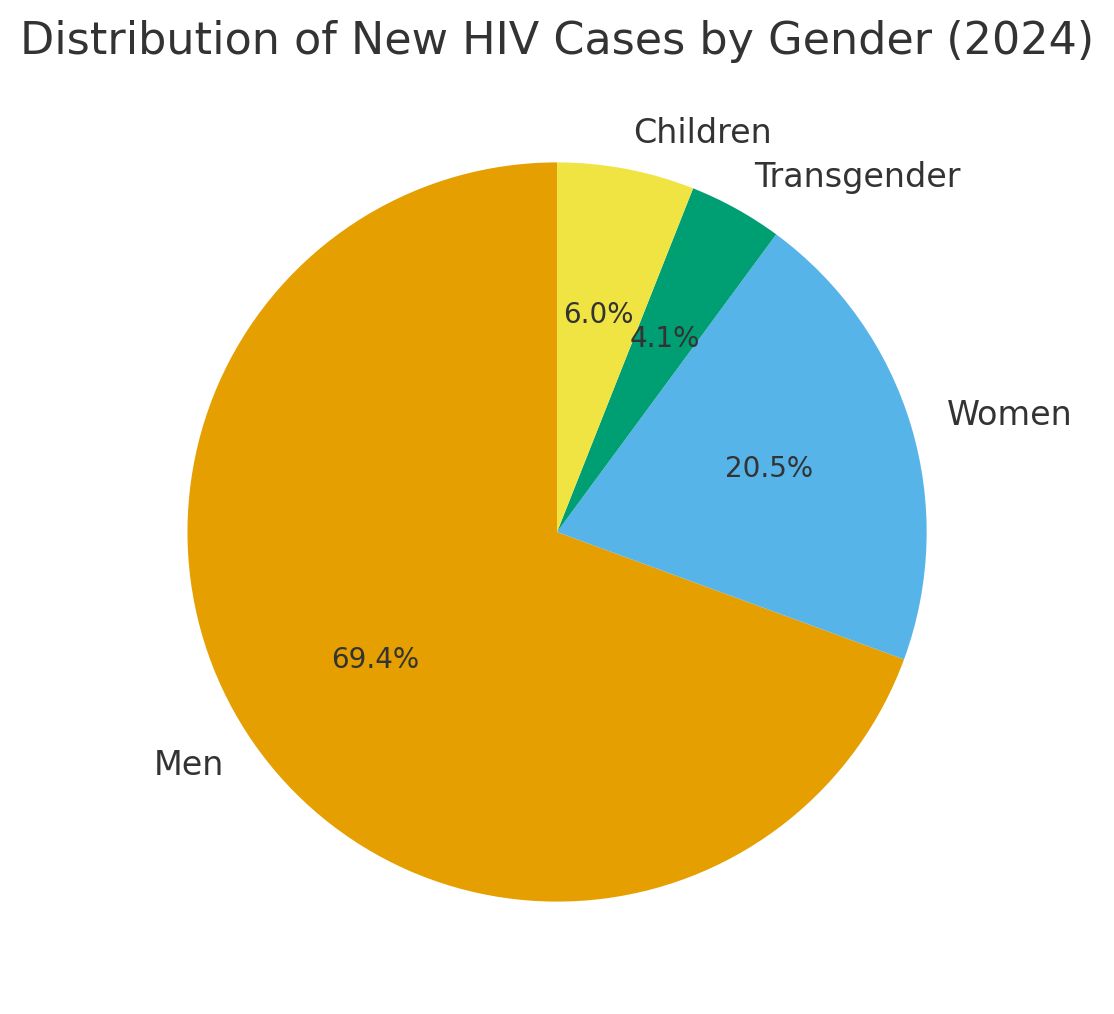

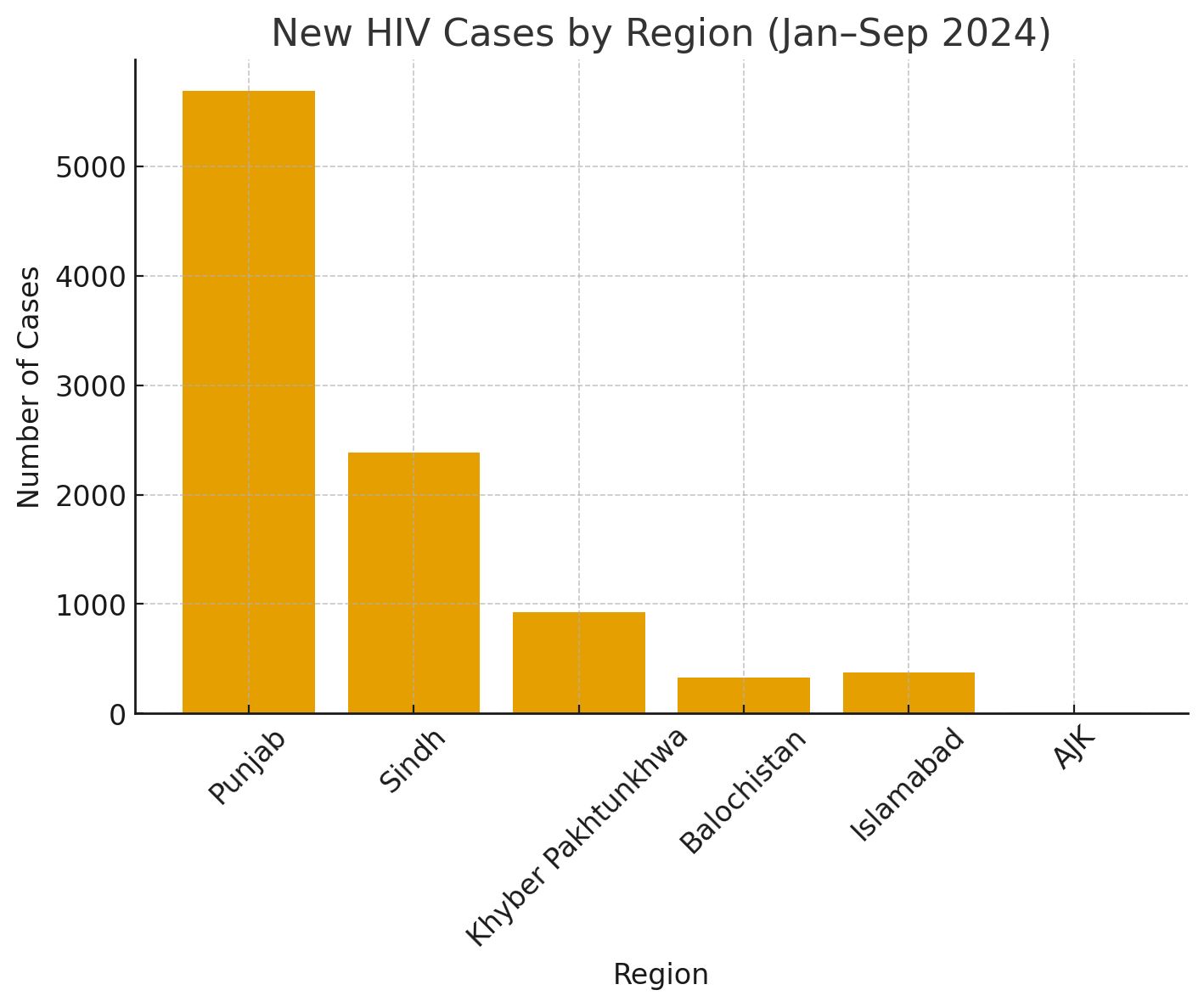

According to official data, men constituted 69.4 percent of the new cases, women 20.5 percent, transgender persons 4.1 percent, and children 6 percent. Punjab recorded the highest number of new infections, with 5,691 cases detected between January and September 2024, averaging 632 new cases each month. Sindh followed with 2,383 new cases, averaging 265 monthly, while Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) reported 926 cases, translating to an average of 103 cases per month. Balochistan recorded 329 new cases, while Islamabad and Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) reported 378 and 10 cases respectively.

Comparatively, the figures for 2023 were even higher, with 12,731 new infections reported nationwide, but the consistent rise in monthly averages for 2024 reflects the worsening nature of the epidemic. Alarmingly, experts have noted a significant spillover of HIV infections from high-risk populations — such as men having sex with men (MSM), transgender persons, injectable drug users (IDUs), and female sex workers — to the general population.

This is attributed to factors such as poor Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) at healthcare facilities, unsafe sexual practices, low awareness, stigma, and risky behaviors like chemsex, a practice involving the use of drugs such as methamphetamine during sexual encounters. Chemsex, in particular, has emerged as a growing concern among MSM, transgender individuals, and sex workers, contributing to the rapid spread of the virus.

“Despite collective efforts, the HIV epidemic is increasing in Pakistan. This demands innovative and sustainable interventions,” said Trouble Chikoko, the UNAIDS Country Director for Pakistan, during a recent meeting with the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Chikoko emphasized the pivotal role that religious scholars and institutions could play in raising awareness about HIV prevention and reducing stigma. “Collaboration with UN agencies and partners is essential to address this crisis comprehensively,” he added.

Commenting on the HIV situation in Pakistan, the Common Management Unit (CMU) for HIV, TB, and Malaria has highlighted its ongoing efforts to curb the epidemic, claiming that 94 Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) centers have been established across the country to provide testing and treatment services. Additionally, awareness campaigns have been launched through mass and social media, including multilingual radio messages and city-branding initiatives to destigmatize HIV testing and treatment. Advocacy efforts involving key government officials and stakeholders have also been undertaken to mark events like World AIDS Day, CMU officials added.

However, these measures have faced challenges. “Stigma remains a major barrier to HIV testing and treatment. Most new infections are still concentrated in MSM, transgender persons, and female sex workers. These groups are often hesitant to seek help due to societal discrimination,” a senior official at the CMU explained.

Officials and experts believe that the use of methamphetamine and other drugs during chemsex not only lowers inhibitions but also significantly increases the likelihood of unprotected sex, further fueling the epidemic. “Chemsex is a hidden yet rapidly spreading phenomenon among key populations in Pakistan. Without targeted harm-reduction interventions, this practice will continue to drive new infections,” the official warned.

In addition to chemsex, other factors contributing to the rising HIV cases include insufficient access to preventive measures, such as condoms and clean needles, as well as limited public awareness about safe practices. The CMU has reported that it is expanding its harm-reduction programs, particularly targeting IDUs, by providing clean needles and syringes. However, the scale of these programs remains inadequate given the increasing number of new infections.

The provincial breakdown of cases underscores the need for localized responses. Punjab, with the highest number of new infections, has been urged to intensify its prevention and awareness campaigns, particularly in urban centers where high-risk behaviors are more prevalent. Similarly, Sindh’s efforts to reduce new infections have shown some progress compared to the previous year, but the numbers remain concerning, especially in Karachi and Hyderabad. Islamabad’s significant drop in new cases, from 611 in 2023 to 378 in 2024, has been attributed to targeted campaigns and improved ART coverage. However, experts caution against complacency, warning that the capital’s success needs to be replicated nationwide to reverse the overall trend.

UNAIDS and CMU officials stress the need for greater community engagement to address stigma and misinformation surrounding HIV. “Community involvement is vital for raising awareness and encouraging testing and treatment,” said Chikoko. With over 1,000 new cases reported monthly, Pakistan is nearing a generalized HIV epidemic. Public health experts urge the government to increase resources for prevention and treatment while addressing barriers to care.

The Nishtar Hospital case first came to light in October 2024, when screenings found more than 20 dialysis patients HIV-positive; by November 2024, the number had risen to around 30–31 confirmed cases. The incident prompted a high-profile response: the Punjab chief minister visited the hospital, several senior hospital officials were suspended, and police investigations later identified dozens of people allegedly involved in record tampering. Provincial authorities also ordered administrative and disciplinary action under the Punjab Employees Efficiency, Discipline and Accountability (PEDA) Act and promised infection-control reviews.